Note: This article was originally published in the Spring 2007 edition of Cutting Edge, the online newsletter of The Meadows.

By John Bradshaw, MA

Pia Mellody joins the company of those who have created highly effective therapeutic models and who can put their theories into practice with unusual skill. Pia’s approach is phenomenological, resulting from her own painful struggle with codependency, as well as from thousands of hours spent interviewing and working out healing strategies with patients at The Meadows. Pia began her unique journey as the head of nursing at The Meadows. In her early days, she suffered from low self-esteem, unhealthy shame, and a hyper-vigilance that accompanied her need to be perfect in every aspect of her work and life. She lived in that lonely place of non-intimacy, polarization, and silent anger that most codependents experience.

Pia decided to get some help for her problems at another treatment facility, where she found the experience not only frustrating but ineffective.

Her problems did not seem to fit into any consistent category of the Diagnostic Manual. When she completed treatment, she continued to try to make sense of her raw pain and confusion, reaching out to others to try to get assistance in alleviating the distress. She was grappling with inner distress exacerbated by a sense of defectiveness, the inability to engage in really good self-care, and living in reaction to other people. Thanks greatly to her, this condition is now called “codependence.” At that time, there was no coherent theory or therapy for the problem.

Early Roots of Codependency

Prior to Pia’s work, some relevant work had been done concerning the reality of codependence. Ludwig von Bertalanffy’s General Systems Theory had filtered its way into several arenas of psychotherapy, notably Ronald Laing, Virginia Satir, and The Palo Alto Group (Gregory Bateson, Don Jackson, Paul Watzlawick, and John Weakland).

In 1957 in Ipswich, England, John Howell concluded that the entire family itself was the problem, rather than just the symptom-bearing individuals. Dr. Murray Bowen developed “The Bowen System” of family therapy. He clearly posited the whole family as the problem, maintaining that the most distressed and under-functioning person in the family triggered the rest of the family into over-functioning behaviors.

The more the family members over-functioned, the more the distressed person under-functioned. Thus, the more the family tried to change, the more it stayed the same. Bowen was convinced that the whole family was in need of therapy. Bowen did not use the word “codependency,” but he emphasized that, like a mobile, every member of a diseased family was dependent on his or her other family members.

Dr. Claudia Black, currently a Senior Fellow at The Meadows, wrote a now-classic book called It Will Never Happen To Me. In it, she described the symptoms she carried as an adult that stemmed from living with an alcoholic father and a co-alcoholic mother. Dr. Black made it clear that her whole alcoholic family was diseased, and that each member was codependent on the alcoholic father. Soon hands-on clinicians like Dr. Bob Akerman and Sharon Wegscheider Cruse (a protégée of Virginia Satir) were describing the symptoms of the adult children of alcoholic families as “codependent,” although no one knows who first used the term “codependency.”

I did a 10-part series on PBS in April 1985 that met with a huge public response. In it, I used a mobile to describe the family system, moving it energetically to show how the whole family is affected in dysfunction, and allowing the mobile a lightly moving homeostasis to show its functional state. I devoted two parts of this TV series to issues I called “codependency,” although my grasp of the concept was still vague and lacked a consistent theory of explanation.

Outside the recovery field, which deals with addictions of all kinds, was the work of Karen Horney and Theodore Millon. Horney’s Neurosis and Human Growth presented many descriptions of a dependent personality. Horney’s description touched upon many of the primary symptoms of codependency, which Pia Mellody later organized into a coherent theory. According to Horney, those lacking healthy adult autonomy and interconnectedness sought their fulfillment and a sense of self from other people. For these people, relating to other people became compulsive and took the form of blind dependency.

Horney used the phrase “morbid dependency.” In the International Encyclopedia of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neurology, John Masters wrote: “I think that mainline academic psychology has not done enough extensive work on dependency as it relates to codependency as an identifiable personality disorder. Codependency is now seen by many to constitute a painful problem for certain clusters in our society. We are on a primitive frontier with regard to understanding codependence.”

In Diagnosing and Treating Codependence, psychiatrist Dr. Timmon Cermak argued that codependency was on par with other personality disorders. “To be useful, though,” wrote Cermak, “codependency needs to be unified and described with consistency. It needs a substantive framework, and, until this is done, the psychological community will not recognize codependence as a disease.”

Enter Pia Mellody

At this point, a young nurse stepped into the arena of modern psychology and made an extraordinary contribution.

One day, Pia Mellody walked around the corner of a building and had a moment of clarity. She thought of AA and how alcoholics start recovery by simply telling the stories of their troubled drinking. They share their experiences and strength in embracing their shame and their first glimmers of hope. Pia realized that hundreds of people had passed through her office at The Meadows with stories very similar to her own. For one thing, a large majority had been abandoned, abused, and neglected as children. Pia had long suspected that her own symptoms stemmed from her traumatic childhood and severely dysfunctional family system.

One day, Pia Mellody walked around the corner of a building and had a moment of clarity. She thought of AA and how alcoholics start recovery by simply telling the stories of their troubled drinking. They share their experiences and strength in embracing their shame and their first glimmers of hope. Pia realized that hundreds of people had passed through her office at The Meadows with stories very similar to her own. For one thing, a large majority had been abandoned, abused, and neglected as children. Pia had long suspected that her own symptoms stemmed from her traumatic childhood and severely dysfunctional family system.

At this point, Pia began interviewing the many people who came to The Meadows with stories of abandonment, neglect, abuse of all kinds, and enmeshment with a parent, the parent’s marriage, or the whole family system. As Pia interviewed person after person, a unique and clear pattern emerged.

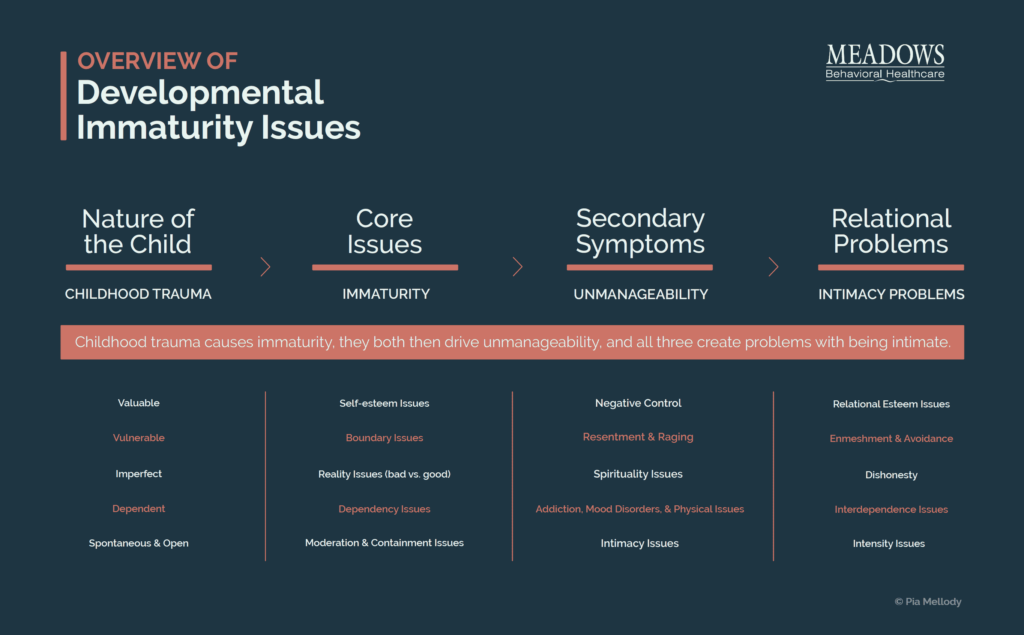

All had five similar symptoms:

- They had little to no self-esteem, often manifested in the carried shame of their primary caregivers;

- They had severe boundary issues;

- They were unsure of their own reality;

- They were unable to identify their needs and wants;

- They had difficulty with moderation.

These symptoms together marked an extreme level of immaturity and a level of moral and spiritual emptiness or bankruptcy. Patients shared their sense of relief in just being able to identify and talk about the distress they were in.

With an interviewing approach fueled by her intuition, Pia Mellody had discovered what she called “codependency.” She had come to understand the word “abuse” in a much broader context than clinicians had previously understood it. Pia also showed how codependents carry their abusive caretakers’ feelings. Our natural feelings can never hurt or overwhelm us; their purpose is to aid our wholeness. Our anger is our strength, a boundary that guards us. Our fear is our discernment, warning us of real danger. Our interest pushes us to expand and grow; our sadness helps us complete things (life is a profound farewell). Our shame lets us know the limits of our curiosity and pleasure; it becomes the core of modesty and humility. And our joy is the marker of fulfillment and celebration. “Carried” feelings lead to rage, panic, unbounded curiosity, dire depression, shame as worthlessness or shamelessness, and joy as irresponsible childishness.

Pia later saw the five core symptoms as leading to secondary symptoms: negative control, resentment, impaired spirituality, addictions, mental or physical illness, and difficulty with intimacy.

Pia believed that alcohol and drug addiction, sex addiction, gambling addiction, and eating disorders must be treated before the core underlying codependency can be treated.

Understanding that addiction is rooted in codependence is another contribution that Pia helped to clarify. Years ago, Dr. Tibot, an expert on alcoholism, saw that there was an emotional core to alcoholism that he called the “disease of the disease.” Pia’s work has certainly corroborated that intuitive insight.

Pia Mellody’s most important contribution may be how she and her groups of suffering codependents worked out strategies for healing. They did this through trial and error. The results were so striking that The Meadows encouraged Pia to develop a workshop titled “Permission to be Precious.” It was an instant success, and Pia began to take it to different cities around the U.S. Soo,n she wrote a book, Facing Codependence, with Andrea Wells Miller and J. Keith Miller.

Later she developed a powerful approach to treating love addicts and their counterparts’ avoidant addictions. Her most recent book, The Intimacy Factor, is the only relationship book that treats the core “grief feeling work” around early abuse, neglect, and abandonment. I believe that other self-help relationship books fail because they do not address these fundamental issues. “Feeling work” involves exposure, vulnerability, and what Carl Jung called “legitimate suffering.” Pia has done her share of that and has the know-how to gently nurture others through this work.

Pia’s work has become the core model in treating addictions of all kinds and the core of codependence they rest upon. She has personally led hundreds, probably thousands, of people suffering from codependency into recovery and wholeness. Pia answered Dr. Timmon Cermak’s challenge to do the work that established codependency as a treatment issue. She not only found a consistent way to conceptualize this source of suffering, but she also found the know-how to address it.

The time has come for a broader recognition of Pia’s art and genius.